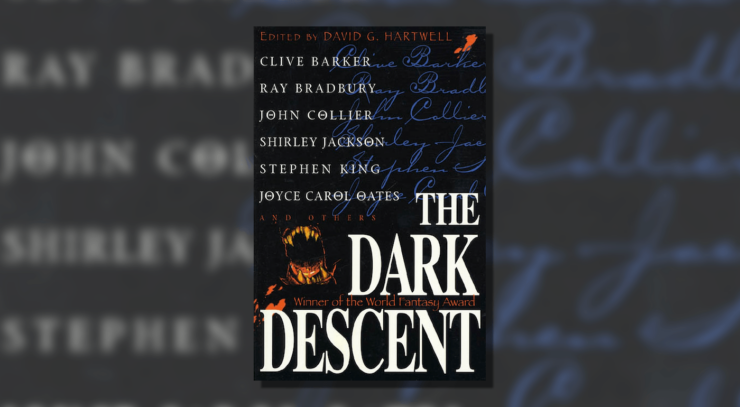

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

Nothing overtly horrific happens in “The Summer People.” There are glimpses, certainly. Shirley Jackson was legendary for her mastery of “quiet horror,” showing small details and slowly mounting dread, creating an unnerving atmosphere around things like a trip to the dentist or an over-designed mansion. It’s a style perfectly suited to the pleasant-seeming surroundings of the Allisons and their lake house, and the passive-aggressive pressure exerted between Mr. and Mrs. Allison and their folksy friends and neighbors. As “The Summer People” opens up, however, those same small details slowly reveal a paranoid fable about why it’s a very bad idea to underestimate those willing to provide you service, and an ominous tale of two peoples’ lives unraveling as their idea of paradise vanishes very quickly beneath them.

As a small resort town gets ready for fall, the Allisons decide that they’ll remain in their summer lake house past Labor Day rather than return to New York City. This is met with shock and surprise by the townsfolk, who claim that staying past Labor Day and into the fall just isn’t done. As the couple stand fast with their desire to stay into the autumn, they’re first met with some basic obstructions as deliveries can’t be made during the fall and supplies are a little more scarce, but more threatening events pile up: appliances stop working, the phone line goes dead, and a letter from their son shows up with strange smudged fingerprints all over it. As a storm gathers on the horizon, the Allisons find themselves isolated from the quaint town, the countryside looking much more dangerous after the summer is over.

The premise is fairly simple: An older couple wants to stay past the end of the summer season, to the objection of the townspeople in a small New England vacation community. They’re slowly cut off from the world, isolated bit by bit, and eventually abandoned in the midst of a storm by family and townspeople alike. They’re even relatively sympathetic for most of the story— after all, all they want to do is stay a little longer before they have to go back to the city and the pressures of their lives. The final image of the story, the two of them huddled around the radio as it dies out, storm raging all around them, generates a lot of pathos for the two. It seems straightforward enough that even Hartwell in his introduction sees it as clear-cut. They transgressed a rule, stepped on tradition, and they pay for it with their lives as they’re cut off and abandoned. Even if it’s (as Hartwell says) “a morality tale without a moral,” there’s a cause and effect. A hidebound cultural idea is transgressed, and thus two people are given a disproportionate punishment for it.

That interpretation doesn’t give Jackson enough credit. Throughout the first half of the story, it’s clear the Allisons are an imposition. They’re consistently insulting to the townspeople, whether it’s wondering if the local general store owner who puts up with their every demand is inbred, to referring to the locals as “simple.” They even directly mock one of them behind his back, chuckling to themselves about the line “good for crops.” Mrs. Allison even has to stop herself from using “city manners” when talking to the gas deliveryman, hinting that she treats service workers back in New York with more active disdain than she does the people of the small New England town. Mr. Allison spends the latter half of the story snapping at people around him for relatively minor inconveniences: mail being late, having to hike to the state road to check the mail, his car breaking down, and the old phone going dead. It’d be easy to write this off as a simple American folk-horror story— a tradition is breached and met with torturous consequences simply for breaching the tradition— but the more Jackson reveals about the Allisons through incidental dialogue and small details, the harder it becomes to do so.

Instead, there is a moral to this. Two higher-class city folk who are used to the “quaint” townspeople of a small New England vacation town serving their every need decide to put more stress on the system for their own ends. They either end up at the mercy of a town that wants nothing more to do with the titular “Summer People” who descend on them like locusts every year, or at the mercy of the elements because they put pressure on an existing system that couldn’t support their whims. While no one would say the Allisons’ fate is deserved, they aren’t entirely blameless in their own downfall. If they’d bothered to listen to or tried to understand what anyone told them, they could have avoided their fate.

That moral is also part of what adds an element of paranoia to “The Summer People.” Sure, all the events could just be bad luck and no longer having access to everything the Allisons relied on over the summer (it’s mentioned that things like newspaper delivery are sporadic anyway), but they could also be hints to the Allisons not to dig in, to leave town with the rest of the summer people. The events are bad enough luck— late mail delivery, things breaking down, a circular about sales in New York being the only newspaper delivery for a week—that they could be normal consequences for the Allisons’ attempt to overstay their welcome. But the way the story turns more and more sinister, the idyllic nature of the lake house and its surroundings leaching out of it with each seemingly minor incident, hints at the possibility of something more.

It’s this interplay of ambiguity, the sinister note underlying what are relatively mundane happenings, and the arguably sympathetic yet decidedly amoral behavior of the story’s characters that uses every aspect of Shirley Jackson’s formidable talent to cement a moral allegory about how one should never overstay one’s welcome somewhere, and to never underestimate the people you consider to be “beneath” you, no matter how “quaint” they seem. At the very least, it’s a wonderfully sinister tale that plays on Jackson’s use of atmosphere and quiet dread to create an ominous, ambiguous story of two lives unraveling in record time.

Please join us in two weeks as we discuss urban myths and urban monsters in Harlan Ellison’s “The Whimper of Whipped Dogs.”

Sam Reader is a literary critic and book reviewer currently haunting the northeast United States. Apart from here at Tor.com, their writing can be found archived at The Barnes and Noble Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Blog and Tor Nightfire, and live at Ginger Nuts of Horror, GamerJournalist, and their personal site, strangelibrary.com. In their spare time, they drink way too much coffee, hoard secondhand books, and try not to upset people too much.